In various industries, producers and product designers depend on a few basic tools to ensure that multiple components are connected and aligned in their assemblies. In this regard, rivets become an important alternative to securely attach multiple pieces.

However, it’s not that all rivets are the same; there are very different types of rivets designed with different designs requirements, made from different materials, served with different purposes, and each with their own individual characteristics.

What is a Rivet?

A rivet is a fixed mechanical fastener that connects two components. A rivet is generally a smooth post with a head at one end, and a tail at the other. The tail is unfinished; once it is installed the tail becomes a shop head or a buck-tail.

In both types, since they are both pieces are installed, a rivet makes a head at both ends. A rivet can be loaded in tension, but rivets are much better at carrying shear loads, which are forces perpendicular to the long axis of the rivet shaft.

The idea of rivets is not new in any sense. Wooden boat builders have used copper nails and clinch bolts to rivet their hulls together for a long time.

These fasteners precede the term “rivet” but while they perform essentially the same function as rivets, they are most commonly named “nails” or “bolts”, with the terminology largely defined by geography and history.

How do Rivets Work?

A rivet can be described as a fastener and is a little bit like a metal pin with a head on one end and a cylindrical stem on the other end which we refer to as the tail.

To install a rivet it is a pretty simple process. First, a hole (drill or punch) is made where the rivet will go. Then the rivet can be inserted. The next step (the magic happens here) is to deform the tail of the rivet, usually pound it or smash it so that it flattens out and expands.

The expansion is typically only about 50% or one and a half times the diameter of the tail but this deformation locks the rivet firmly into place.

When the process is finished, the deformed tail typically resembles a type of “dumbbell” shape, which secures the joint. Riveting is not limited to a fastened connection it can also consist of lap joints and butt joints and according to the application, various arrangements such as single rows, double rows, and zig-zag can be provided.

What is the Riveting Process?

Riveting is a traditional forging process people use to join any number of different pieces together, often called a rivet.

Essentially, the rivet goes through the aligned holes in the pieces being joined, and then both ends of the rivet are deformed down almost like hammering the tips flat so that the whole assembly will stay sturdy.

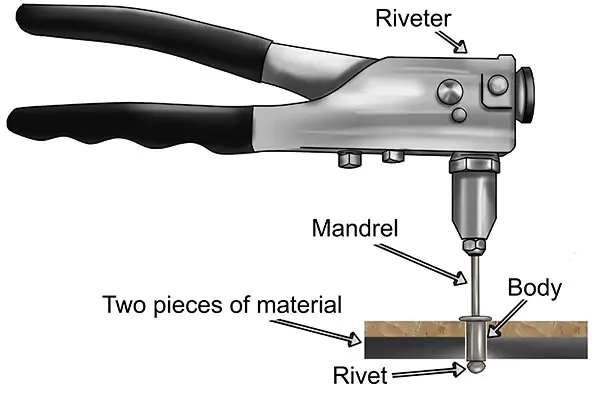

There’s a type of rivet called a pop rivet, sometimes also called a blind rivet or hollow rivet. Pop rivets are a great option when you can only access one side of the project, which to be honest occurs very often in real-life repairs or projects.

To use a pop rivet, you will need a pop rivet gun – a tool that can pull the mandrel (that pesky little rod that is fixed inside the rivet), up into the body of the rivet to deformed the backside of the rivet, which expands the rivet and allows it to grip the material that you can’t see.

Once the mandrel is pulled with a certain amount of tension, the mandrel will snap off, and you will be left with a strong, tight joint.

Pop rivets are very flexible, too! They are often used as substitutes for other fasteners, including nuts, bolts, screws, and even welding or gluing. Pop rivets are quick, reliable, and practical in places where other forms of fastening would just be a headache to use!

Riveting Definition

Riveting is one of the types of forging process that involves joining parts together via a metal fastener, or rivet. Those parts are assembled together using a mechanical force established by the rivet that when set, produces a complete and permanent connection.

Material use in Rivets

While toughness and ductility should generally be prioritized when considering material for rivets. Rivets are commonly formulated from low carbon steel, nickel steel, brass, aluminum, copper, and numerous materials in every day practice.

When discussing applications that need both strength and a liquid-tight application, steel rivets are generally advised to use.

Types of Rivet

There are Different Types of rivets:

- Blind rivets.

- Solid/round head rivets.

- Semi-tubular rivets.

- Oscar rivets.

- Drive rivets.

- Flush rivets.

- Friction-lock rivets.

- Split rivets

- Threaded rivets

- Self-Piercing Rivet

1. Blind Rivet

Blind rivets, or break stem rivets, are basically tubular fasteners with a mandrel. The mandrel runs right through the middle of the rivet and that’s how you use a blind rivet, you pop it into the pre-drilled hole in the pieces you are tying together.

Then you use a special tool that pulls the mandrel through the body of the rivet causing the blind end to swell. The mandrel snaps off when it has finished.

This is why blind rivets are so useful; unlike solid rivets, you do not have to have access to the other side of the rivet. When working from one side of the joint perhaps because the other side is obstructed or difficult to access blind rivets are a great option.

Hence the name, blind, essentially you are working blind to the blind end of the rivet.

There are a variety of different blind rivets, standard, structural, closed-end, etc., so they’re a very versatile solution for a lot of applications, particularly when you don’t have full access.

2. Solid Rivet

Solid rivets are truly the original fastener. They couldn’t be more simple: just a solid shaft and a head on one end. Once the rivet is in place, you hammer, or use a rivet gun, on the end of the rivet that has no head to deform the rivet and to lock everything into place.

There’s a reason solid rivets have survived into the present day they have been around since the Bronze Age, according to archaeologists! When jobs must be truly trustful and reliable for safety purposes, engineers turn to solid rivets. They are used on everything from bridges to airplanes!

You will generally find solid rivets with either a round (universal) head and a countersunk head (generally 100°); it depends on the job at hand.

3. Drive Rivet

Drive rivets, in a clever twist on the blind rivet concept, differ from blind rivets because they have a short mandrel protruding from the head of the fastener.

The installation of drive rivets very simple; when the rivet is in the hole, you simply use a hammer to drive the mandrel in; this flares out the inside end of the rivet and locks it into place.

Drive rivets are popular for applications where you want to avoid drilling a hole clear through the material, like when you’re attaching wood panels and want a clean, visually appealing surface.

Drive rivets are not limited to wood either; you will see them used with plastic, metal, and other materials. You also do not need fancy tools to install them—a hammer and maybe a backing block are all you need.

Drive rivets should also be noted as not delivering a high clamping force as other fastener types, but they are often the fasteners of choice for instances like nameplates which are going into a blind hole.

Some people even refer to drive rivets as “drive screws”, especially when they are referring to the little fasteners on a nameplate.

4. Semi Tubular rivets

Semi-tubular rivets appear very similar to solid rivets; however, the significant difference is that the end opposite to the head has a hole. Due to this small design change, when force is applied, the tubular portion of the rivet (the portion with the hole) will flare open.

Due to this relatively unique design, the force required to install a semi-tubular rivet is approximately one quarter of the force required to install a solid rivet. For this reason alone, semi-tubular rivets are a good choice for many applications.

Because swelling can only occur at the tail end of the rivet, semi-tubular rivets are generally used at pivot points or motion points. In terms of installation, there is a full spectrum of tools to install semi-tubular rivets – from the most rudimentary prototyping tools to fully automated systems.

Common installation tools include handsets, manual and pneumatic squeezers, kick presses, impact riveters, and fully automated PLC-controlled robots. Among these installation tools, the impact riveter will probably be the one you experience most often.

As for the applications of semi-tubular rivets, you will find them on a wide range of products and there are quite a number of products that include them. Semi-tubular rivets are quite common in lighting fixtures, brake assemblies, ladders, office binders, HVAC ducting, a variety of mechanical products, and many electronics.

5. Split rivets

When it comes to softer materials—woods, leather, and plastics—split rivets tend to be the rivets of choice. Split rivets are the standard “home repair” rivets most people are used to finding in their home repair kits.

What makes them special is their body, which is split and has a sharp tip meant to cut its own hole through softer materials like leather, fiberboard, plastics, or softer metals. However, split rivets should not be used in critical or high-stress applications.

6. Threaded rivets

Threaded rivets (or rivet nuts or threaded inserts) can be a clever way to create a durable, permanent thread in a sheet material (or wherever access is confined to a single side).

The concept is quite simple; the rivet has an internally threaded mandrel and a round body that has been machined flat on two sides to avoid jamming the tool and allow the tool to grip and rotate it.

In most cases, the head takes on a hex shape to prevent the body from spinning while the mandrel is torqued and ultimately snapped off. This provides a strong, reliable thread, where you didn’t think you could find good threads!

7. Oscar Rivet

Although initially rivets look similar to blind rivets, Oscar rivets have splits along their hollow shaft. When the mandrel is pulled into the rivet during installation, the splits allow the shaft to flare outward which establishes a wide bearing area on the blind side of the rivet away from the access point.

When the rivet flares out it will not only help to minimize the chance that it will pull out, it makes Oscar rivets particularly good for actual applications where vibration is present and access to the back side is restricted.

There is also an Olympic rivet, which works slightly differently. Olympic rivets draw an aluminum mandrel into the rivet head; after it has been squeezed, both the head and mandrel are shaved off to be flush with the surface. The end result is very similar in appearance to a rivet driven with a traditional brazier head.

8. Flush Rivet

Flush rivets are usually selected for the external side of a metal structure when appeance is important or there is a need to minimize aerodynamic drag.

With flush rivets, the rivets are installed in countersunk holes, so when the flush rivets are set, the head is level with the surface of the material. Flush rivets are also called countersunk rivets.

You will find flush rivets in application on a wide variety of aircraft skins. The outer design of the flush rivet has a significant impact to reduce drag and turbulence during flight.

In some cases, the rivets are too thick and require additional machining or sanding to smooth the airflow over the rivet once correctly installed.

9. Friction-lock Rivet

Friction-lock rivets are similar to expanding bolts, in that, when tension is applied, the shank will break off below the head. The head (the set) can be a dome shape or flush, depending on the application.

The Cherry friction-lock rivet is one of the original and the most widely used blind rivet in aircraft. The Cherry friction-lock rivet started as two types: the hollow shank pull-through type and a self-plugging type.

While the pull-through type is no longer used, the self-plugging Cherry friction-lock rivet is still sometimes used in lightweight aircraft repairs today.

Friction-lock rivets should not be used as a direct replacement for solid shank rivets of the same nominal size. If a friction-lock rivet is to be used as a substitution, it must be at least one size larger in diameter.

One of the issues with using friction-lock rivets is; if the center stem comes loose from the friction-lock housing due to vibration or damage, the integrity of the rivet will be compromised.

10. Self-Piercing Rivet

Self-pierce riveting (SPR) joins two or more substrates with a specific rivet design. The ability to be installed with no pre-drilled holes is a principal advantage when compared to other common rivet styles: solid, blind, or semi-tubular rivets.

This feature is almost always a benefit in terms of assembly; and SPR is very attractive for applications that prioritize speed.

The rivets are cold-formed into a semi-tubular shape with a hole that extends up and out from the end opposite the head. When examining the tip of a self-piercing rivet, you will see a chamfered poke; even though it is a small detail, it plays an important role in allowing the rivet to pierce the materials during installation.

During the riveting operation, either a hydraulic or electric servo-driven tool pushes the rivet through the materials joined together, and at the same time a upsetting die is positioned against the bottom side of the bottom sheet to accommodate the displaced material. This is an important aspect of the operation because it allows for tight fitting of the joints without excessive deforming.

During the installation process, the self-pierce rivet extends completely through the top sheet, potentially several sheets, but does not fully penetrate the bottom sheet. Here, it is important to mention again that the tail of the rivet does not puncture through the bottom sheet.

This means that the resultant joint is frequently water-tight or even air-tight, which is significant for example for the automotive industry.

When the rivet installation operation is completed, the die on the bottom of the joint structure allows the tail end of the rivet to flare out creating a locked condition to the bottom sheet.

The end result is a strong button-like profile on the bottom side and a structurally strong joint which also protects against leakage.

What is Rivet Joint?

A riveted joint creates a permanent connection in two primary parts that are connected by a rivet. The rivet is usually oriented with the head on top and it will have the tail extending down below the part.

Riveted joints function the same way as bolted joints and it has important differences for the functionality for CFRPs and aluminum alloys.

With a rivet, the fastener is cycled through the composite, and in partial connection to the aluminum beneath. Then by using a die the rivet tail is flared out against the inside the aluminum alloy, locking the parts together on strong, permanent connection.

Types of Riveted Joint

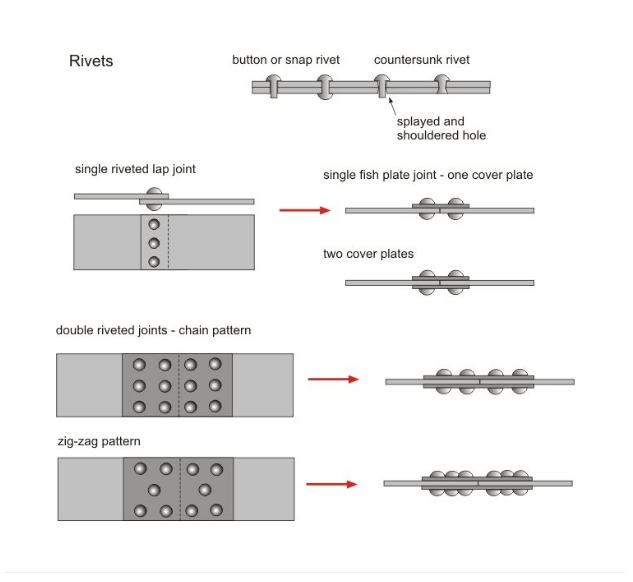

There are essentially two main types of riveted joints, lap joints and butt joints. The choice of joint type is determined by how the plates are assembled.

Lap Joint

A lap joint is a simple concept where one piece overlaps another. You can find lap joints used in a variety of materials including wood, metal, and plastic. For example, when woodworking, a lap joint is a common way to join two pieces of wood.

Depending on your needs, you can create either a full lap, in which two pieces completely overlap, or a half lap, in which each piece is cut to half its thickness at the lap joint so that they fit together snugly.

Butt Joint

Conversely, a butt joint is somewhat different. A butt joint merely places the two principal plates, end to end, so that the edges touch each other. However, that is not sufficient to secure the connection, so a cover plate (also known as a strap) is placed over the seam.

The cover plate can be connected to one side of the joint or both sides (depending on the required strength), and everything is riveted together to ensure that the plates do not become misaligned. The joint is designed with this method in mind because the plates “butt” against each other, rather than lap.

Butt joints are classified into the following types:

- Single Strap Butt Joint: In a single strap butt joint, the edges of the main plates are placed together (end-to-end). In this type of joint, there is only one cover plate, and is provided on one side of the main plates. Once everything is joined together, rivets are used to index the joint. This joint is fairly simple and widely used in situations where modest strength is acceptable.

- Double Strap Butt Joint: A double strap butt joint is similar to a single strap butt joint, in that the main plates will butt against one another, but with a double strap butt joint, there are two cover plates, one on each side of the joint. Each plate can then be riveted down firmly, providing more strength, stability, and loading orientation than the single strap butt joint. Additionally, as rivet placement can vary on double strap joints depending on if rivets are in single or multiple rows, we notice the types of joints can vary further in rivet rows, number and layout.

- Chain Riveted Joint: In a chain riveted joint, the rivet rows are set out to where each rivet in each row is directly opposite a rivet in the neighbouring row. Rivets arranged in this manner forms two straight, parallel lines of rivets above and below the joint, creating a strong hanging joint, able to distribute a load equally, and can plainly be visually inspected.

- Zig Zag Riveted Joint: A zig zag joint, instead of rows that don’t line up at all, stagger each rivet, not allowing for rivets from two rows to align directly with neighbouring rivets at all, and is actually a more favourable joint, as load resistance can spread out the stresses, more often than not, when a stronger joint is required, we see zig zag joints.

- Diamond Riveted Joint: Diamond riveted joints are most commonly found in butt joints, and finally post that concept, so the rivets are still in a joint in pain, Diamond riveted joints are apart, as opposed to directly opposite at the edges of the butt joint, and are angled wider at the joint, forming two handcrafted diamonds with the points together, where accordingly, the rivet rows also are made even when they wider than they appear, purely specific loading or stress diagram for choosing a diamond shape joint.

Application of riveted joints

These are some applications of Riveted joints:

- Rivet joints are a permanent form of fastening and are primarily used to connect sheet metal or shaped rolled metal parts.

- Rivets are often found in aircraft construction; particularly in aluminum components.

- In the bus and trolleybus field rivet joints typically provide a joint that must withstand substantial loading.

- Where there is a variety of metals involved that do not weld easily rivets are a viable alternative.

- In addition rivets can be used to join completely different materials, including asbestos friction lining to steel.

- In some instances rivets provide a safe joint to avoid heat affected area associated with welding.

- In addition, welded joints are usually poor in their resistance to vibrational modes, and, if some form of vibration damping is used, rivets, in most instances should be the preferred option.

- Rivets will be used with joining, lap, abutment and double-cover plate joints.

- For many applications rivets will provide an excellent compromise between lightweight, cost effectively and provide substantial strength.

- With some alternative joining methods to rivets as available, rivets are still used in the construction of metal bridges, hoisting cranes, boilers and pressure tanks.

- Rivets are still a preferred joining alternative for components in the construction of many types of structures including aircraft, boilers, ships, boxes and many other enclosures.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Riveting

Benefits of Riveting

- Cost-Effectiveness: One practical advantage of using rivets is their affordability—manufacturing them doesn’t require much expense, making them an economical choice for various projects.

- Versatility Across Metals: Rivets are suitable for connecting not just ferrous metals, but also nonferrous options such as aluminum and copper alloys, which broadens their applications significantly.

- Compatibility with Nonmetals: It’s not just metals—rivets work quite well for joining materials like wood, plastic, or even asbestos sheets, which makes them handy for a range of engineering and construction scenarios.

- Joining Dissimilar Materials: Perhaps one of the most convenient features is their ability to join materials that are completely different from each other, such as aluminum plates to copper plates, without major complications.

- Flexible Application: Another thing that stands out is how rivets aren’t limited by position—they can be used for joints in any orientation, whether vertical, overhead, or at awkward angles.

- Environmentally Friendly Process: Since there’s no welding involved, you don’t have to worry about harmful fumes or gases. This makes the process safer for workers and better for the environment.

- Reliability Under Stress: When it comes to joints that will be exposed to lots of vibration or sudden impacts, riveted joints often hold up better and are more dependable compared to other joining methods.

- Mechanical Strength: Riveted joints typically offer high shear strength and decent resistance to fatigue, which is why they’re commonly chosen for structural applications.

- Lightweight and Corrosion Resistance: If weight is a concern, aluminum rivets are much lighter than typical bolts and screws, plus they offer excellent resistance to atmospheric and chemical corrosion.

- Minimal Thermal Impact: Since there’s no melting or uneven heating and cooling during the riveting process, the risk of thermal damage is minimal. This is especially important if you want to preserve protective coatings on the materials being joined.

- Simplified Inspection: Checking the quality of a riveted joint is usually more straightforward than inspecting welds, making quality assurance easier for the team.

- Easier Dismantling: If you ever need to take the joint apart, riveted connections typically come apart with less damage than welded joints, which can be a huge plus for maintenance or future modifications.

Limitations of riveting

- Riveting generally requires more physical labor than welding. Riveting not only requires the joining of two pieces, it requires added effort to measure, mark, and drill the holes necessary for the rivets. All of this additional work adds up to increased labor costs for riveted joints.

- One disadvantage of the riveted connection is the stress that is concentrated at the rivet holes in the metal plates. In time, these concentrated stresses can become the weak link in the system if the structure is subject to changing or significant loads.

- When holes are drilled for the rivets, the original strength of the plate is compromised. This sacrifice of strength typically requires engineers to make the plates thicker than they would otherwise make the plates, and the necessity to overlap the plates for alignment requires even more metal for riveting.

- Another consideration is weight. Generally, riveted joints weigh more than welded joints because of the rivets, and possibly strap plates as well. If you are trying to keep weight in mind, additional weight to consider is never good.

- From a design perspective, riveted joints are also bulkier, since riveted or brazed joints generally have a larger cross section when you include the head of the rivet. Visually, riveted connections appear less sleek than welded joints (if appearance is a concern).

- Riveted joints do not exhibit the same characteristics as a welded joint when it comes to an airtight or watertight seal. Unless hot riveting occurs, or a sealant is added, riveted joints can develop small leaks at the connections of the joined plates.

- Finally, riveting is a noisy activity since repetitive hammering will can be quite loud and disruptive to others. Welding can also be noisy but generally is quieter than riveting.

Types of Failures in Riveted Joints

When it comes to riveted joints, there are plenty of ways things can fail, and it is important for anyone using, studying or thinking about these joints to be aware of their failure modes. Let’s take a look at them:

- Shear failure: In shear failure, the rivet itself shears off, like scissors cutting paper. In other words, the forces that try to slide the plates past each other become too much for the joint, and the rivet shears off in the direction of the excess lateral forces.

- Tensile Failure of Plates: Tensile failure occurs when the plates supported by a rivet fail to resist the separation (tension) forces developed across the rivet. If the tension force is too high, that an amount of stretch occurs, until eventually complete tensile failure results when the plate is broken.

- Crushing Failure of Plates: Crushing or crushing failure refers to failure of a plate material surrounding the rivet by the rivet itself. This occurs when enough pressure causes the rivet to crush the plate, which ways increase the diameter of the hole that matches the rivet, or crushing the plate in itself.

- Shear Failure of Plates in the Margin Area: In addition to the rivets, the plates themselves can fail in shear between the edge of the plate and the nearest rivet (known as margin). If the margin is too weak, shearing failure may occur.

- Tearing of Plate in the Margin Area: Finally, without enough area between the edge of the plate and rivet, tearing failure may result from the edge of the plate, just like when you open an envelope that was sealed too tightly!

FAQs

What is the purpose of a rivet?

They are used to join two or more materials together and form a joint that is stronger and tighter than a screw of the same diameter could be. Riveting is used in all types of construction today, metal is the most commonly riveted material. But wood, clay, and even fabric can also be riveted.

What is a rivet joint?

In simple terms, a riveted joint is a permanent type of fastener used to join metal plates or rolled steel sections together. These joints are extensively used in steel structures or structural works such as bridges, roof trusses, and in pressure vessels such as storage tanks & boilers.

What is rivet in engineering?

Rivet, headed pin or bolt used as a permanent fastening in metalwork; for several decades it was indispensable in steel construction. A head is formed on the plain end of the pin by hammering or by direct pressure.

Why are rivets no longer used?

Rivets in the metal structures now seems archaic and from other times. However, rivets were extensively used for metal structure in the 19th century and in the first half of the 20th. The use of high-strength bolts displaced the rivets in the second half of the century and nowadays rivets are no longer in use.

Is a rivet stronger than a screw?

Compared to screws, rivets hold much better. They are impossible to open and won’t shake loose. This is because the screw only has a head on one side whereas the rivet is supporting both sides. This is also important in the transport process where the frame is subject to vibration.